The new Caucasian chalk circle: Georgia`s surrogate motherhood business

“The difference between a serial killer and a paid surrogate is that one kills over and over, while the other gives birth over and over.” We don’t know if this is a task or an explanation from the Georgian colleague we meet in a Tbilisi cafe on our first evening. We’d been preparing for weeks, corresponding with international and Georgian women’s rights organisations, Georgian government bodies, surrogate mother brokers, but we still arrived empty-handed. All our requests had met with uncertain answers and we’d only managed to schedule one interview. Clearly nobody was in a rush to speak.

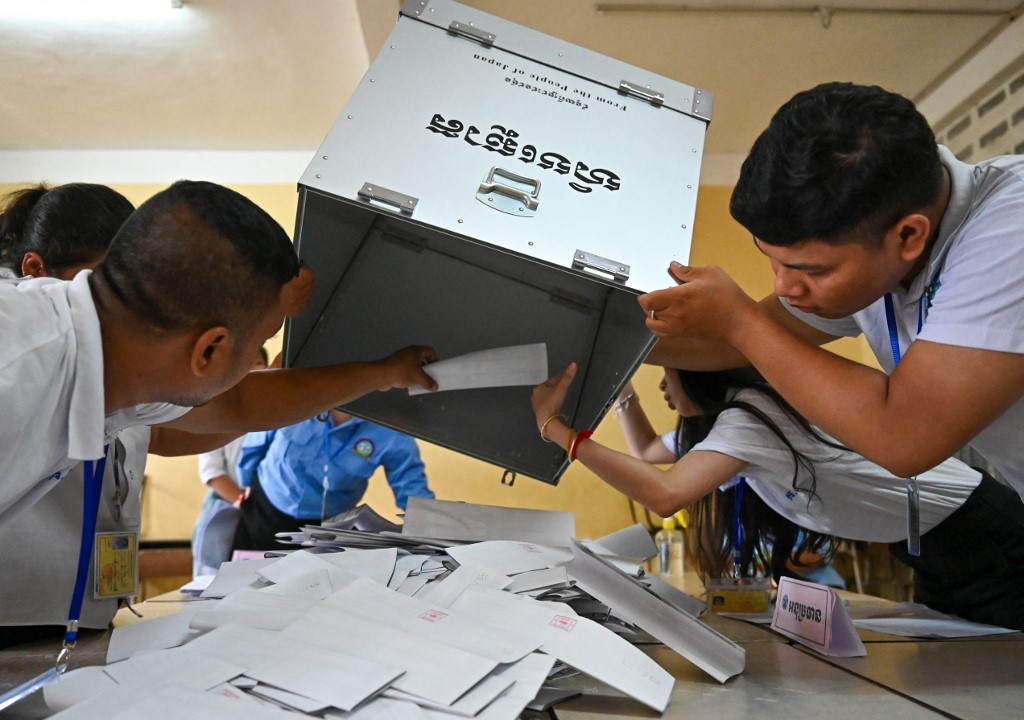

“It’s a tabu,” explains the only journalist prepared to speak to us. Surrogacy and children borne of surrogates have been condemned by Patriarch Ilia, the head of the Georgian Orthodox Church, the journalist reminds us. In his January 2014 Christmas address he said children conceived and born in this way can have “problems” in adult life, while families who raise such children will not happy. The patriarch’s words shooi Georgia’s deeply religious society, which is heavily involved in the surrogacy industry. Politicians and public intellectuals protested against his words, including health minister Davit Sergeenko, Tbilisi’s mayor Gigi Ugulava, and even Tamar Chugosvili, the Assistant to the prime minister of Georiga on human rights and gender equaliti issues. “Every child has the right to life and happiness,” the protesters said. On January 8, protesters clashed with the patriarch’s supporters in front of his official residence. Police had to intervene. Over the past three years, not only have the passions not been dulled, but the number of surrogate births has continued to grow, raising the stakes for everyone discussing the Georgian system. That explains people’s caution when talking with journalists arriving from eastern Europe. There isn’t a complete absence of information: to our surprise, the first person to talk to us is Mariam Kukunashvili, founder and head of the New Life in Georgia centre. This surrogate broker is the best-known commercial success story in the market. Kukunashvili is well known in the media, a professional dancer, and regarded as one of the 10 richest Georgian women. New Life in Georgia has been working for nine years and has built up an international network, with agencies in Nepal, Mexico, Cambodia and Poland.

Kukunashvili is more than just a businesswoman. She also advocates a “philosophy” of surrogacy, and she is criticised for that in Georgia. New Life in Georgia was accused four years ago of illegally smuggling surrogate-born infants out of Georgia to European couples. Not that that damaged her business. Since, a film has been made about her, entitled Mother of 5,000 Children, and she now works on several continents simultaneously. She made time to give us a long interview. We worried that she would use the opportunity for advertising purposes – which is indeed how the question-and-answer session starts. “Everyone has the right to have a child,” she says almost by way of introduction, repeating a line familiar from surrogate brokerages’ marketing brochures. Georgia’s laws, she adds, place almost no restrictions on who can be a “client” or a “candidate parent”. Is there no assessment of the adopting parents’ suitability, we ask. “Who gets to decide who can and can’t be a parent?” she asks in reply.

There is one restriction in Georgia: gay couples will not be served.

Bargain wombs

New Life in Georgia’s global network found a solution even to this: the gay candidate parents are treated in clinics in countries where there is no such restriction. “We are prepared for most cases. We send HIV positive parents to Mexico, where there are possibilities for surrogate parenthood. Spanish parents can’t get the necessary documents from the consulate in Mexico to take their children back home, so we send them elsewhere, for example to Georgia.” Specialist literature describes these procedures using terms like “surrogacy or ovary donor tourism” or “offshore surrogacy”: the aim is to allow the buyer to avoid local legal restrictions, find international backdoors and get a child for the best possible price. Over the past 15 years, there has been a surrogacy boom, and in consequence internationally regulated adoptions have fallen by a third. According to a 2012 report by the standing committee of the Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law, the volume of commercial global surrogacy transactions rose 1000-fold. There are 3,000 clinics in India currently, earning 2.3 billion billion dollars in 2012 according to the Indian Chamber of Commerce. India is the cheapest provider, also serving gay and single people. For $6-7,000 you can rent a “womb”, as surrogate mothers are called in the trade’s own jargon. A full surrogacy package is a lot more expensive, but still rarely exceeds $20,000. The surrogate mother’s fee, paid in installments, and medical fees also contribute to the cost. It costs more to have a Caucasian, rather than Indian ovary donor. The full administrative costs and travel documents for the infant can be settled for another $200-500. In the U.S., this is far more expensive. There, surrogacy costs at least $110,000, rising to $170,000 at some clinics.

100 percent business

Price explains why Georgia has become so popular. Here it is more expensive to get a surrogate mother than in India. The mother can expect to be paid $10-12,000, depending on whether she will give birth to a single child or to twins. But the costs are barely higher, while the egg donor is Caucasian as part of the “basic package”. Georgian surrogates are cheap, and enjoys barely any rights at all under Georgian law. The surrogate mother is not mentioned in the birth certificate, and she enjoys no rights relating to the child even if she cancels her contract with the buyers. This, Kukunashvili points out, is not the case in Nepal, Thailand or Cambodia. Surrogate mothers are paid in instalments, and conditionally, with the transaction flowing directly from the client to the woman bearing the child. Kukunashvili says this is necessary to avoid accusations of the surrogate mother not receiving her promised fee. But if the woman gives birth prematurely, or if there are complications, or if some kind of dispute emerges between the clients and the surrogate mother, then the client may refuse to pay, or pay only part of her fee. “What motivates the women,” we ask. “Money, or is there an element of charity?” The answer is clear: “The motivation is entirely money,” says Kukunashvili, who nonetheless rejects the suggestion that the women are being exploited. “If you look at World Health Organisation statistics, you can see that there are many professions that are injurious to health or that can cause death. More than 200,000 construction workers die in the U.S. each year. Surrogacy isn’t like that.” But she gives a more complex answer when asked about the relationship between the surrogate mother and the infant or foetus. There is an emotional bond between the woman bearing the child and the infant, she says, but it is made clear to the surrogate mothers from the first instant that the child in their womb is not theirs. Her own relationship with the women who bore her children is that of “two women who helped and help each other,” she says. Whose is the child, we ask, whose ‘property’? “The child belongs to the person who wants it,” she says. “Motherhood is a social role that you either accept or reject. The important thing is not that my child comes from a surrogate mother or that I adopted him or her, or that she was brought in from the street. If I want the child to be mine, then that child is mine.” It appears that this desire (and the invested capital) is what drives this fast-growing market for surrogacy. And the international environment is growing ever more accepting of this, she tells us. A European client can obtain travel documents from their embassies for an infant born to a Georgian surrogate within five to six weeks. (Kukunashvili uses a specialist to arrange this). The British, U.S. and Australian embassies demand a DNA test, but others don’t, she tells us. The child frequently has no biological relationship to the female client, but there are frequently cases where the child comes from the ovaries of an anonymous donor, meaning that it has no biological link to either parent. What, we ask, would she change in Georgia’s law on surrogacy? She tells us she would set limits on who can be an egg donor and how often, and she would also set limits on the maximum age of clients. “Adopting a child aged over 60? Someone needs to raise that child, after all.” Would she not try to strengthen the rights of surrogate mothers? But she rejects the idea, even though we know for sure that her company provided legal support to surrogates who did not receive the fee they were promised. “What do you think of the European practice of calling these surrogates ‘technical mothers’?” we ask. She is less strict on this point: “I don’t think that’s right. For a successful pregnancy you need care and attention, and that can’t be achieved via purely technical means. If we look at these women like that, then we open the door to exploitation.”

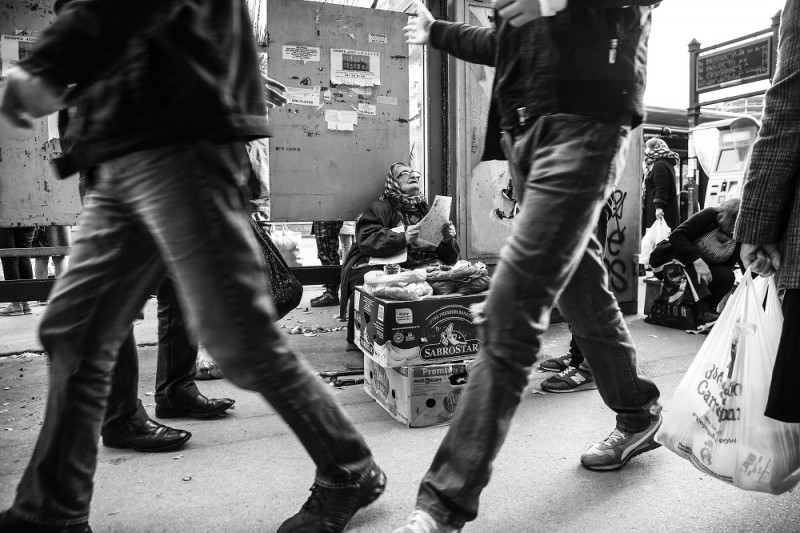

New Life in Georgia’s elegantly furnished offices are on housing estates. Brass plaques with the company name shine above the entrances to the surrogacy centres, and the office manager bids us farewell in a British accent. But the moment we walk outside, elderly Georgian women with bent backs swathed in headscarves and winter coats beg attempt to sell us their wares. It’s a very different world out here. Fruit, vegetables, home-made cakes, knitted clothes, souvenirs, antiques for sale on every corner. On Liberty Square, an old woman offers spices wrapped in paper and plastic bags from a collection she keeps in a rickety old pram. The gilded statue of St. George signs in the distance. Everything is for sale on the streets of Tbilisi. Huge crowds are looking to earn a few lari. And there’s nothing to suggest that a multi-million dollar industry is functioning in the neighbourhood.

Surrogacy as flight from domestic violence

Our next meeting is much harder to get: Nato Shavlakadze, the president of the Georgian Anti-violence Network, is only prepared to receive us after I write the last of many very assertive letters, making clear that I am not there to drum up a scandal, nor to build my own career, but to investigate an extremely important social issue of importance to Georgia and Europe. In their office in a courtyard apartment building it turns out they have decided to ‘test’ me: they need to meet me to decide if they trust me enough to share their knowledge about surrogacy. Kukanashvili had told us that just because some Georgian women chose to be surrogates for financial reasons, we should not think only the very poorest did so. Some just wanted to improve their standard of living or send their children abroad to study, New Life in Georgia told us. But Shavlakadze said surrogate mothers were frequently the victims of domestic violence. Several women living in her non-governmental organisation’s (NGO) safe house had ended up in surrogacy programmes. Not because the NGO had pushed them into doing so but because socially deprived single women had few other ways of surviving. “We’ve had cases where we rescued a woman from a people smuggling, drug mule network. She was raising her two children alone and was in any case disadvantaged as someone who had been abused and raised in a state children’s home. She became a surrogate mother, and they didn’t even pay her.” One crisis brings on another, Shavlakadze said. “We can provide some security to these women in our safe house for a few months, but where can they go afterwards? They establish networks, and the victims follow each others’ examples, and so they end up in the system. As a surrogate mother they at least have a home for the duration of the pregnancy, and after a few births they can even buy a home.”

She urges us to visit their safe house in Tbilisi, but we have no idea what a difficult task that will turn out to be. We head to another housing estate, and after more than an hour we still haven’t found the address near a car repair workshop we’ve been given. Eventually they send a car for us. The house is at the end of a blind alley, behind high concrete walls. Ia Khutsishvili, the manager, greets us. She’s a smiley, friendly woman, but in just a few words she summarises who lives here and why. While we were there, a mother of five was given a place in the house. Her face was bruised, and the wounds had been stitched up. Her youngest son was a year and a half old. Another mother lived there with her daughter. She was a former journalist whose parent-in-law had attempted to kill her after her husband’s death. The centre, financed by international foundations, can give shelter for eight months at most. Afterwards, the needy must make their own arrangements. That’s easier in Tbilisi, we are told. It’s harder in the countryside, from where most of the surrogate mothers also come. So we head out into the provinces, to the town of Akhalzikhe near the Turkish border where many ethnic Armenians live. Here we are shown another crisis centre and safe house.

Traditional values and atomic waste

The Democratic Women’s Coalition provides legal, medical and psychological support to victims of domestic violence, the organisation’s Marina Modebadze explains. It is primarily young, single women living in extreme poverty who end up as surrogate mothers, she says. Some 25 percent of the marriages in the region are forced marriages that are often ended by the male partner. Women who then find themselves alone then become financially vulnerable, tempted to resort to surrogacy as a way of escaping poverty. The crisis centre’s psychologist says women and girls in closed, provincial communities, especially Armenians who grow up in a very traditional environment, are particularly endangered. In their cases, the community is very unforgiving of extra-marital pregnancy and divorced women are also looked on with suspicion. If somebody ‘gets into trouble’, they leave their home and head for Tbilisi. If she then resorts to surrogacy to keep afloat, she tries to keep it secret, but if that doesn’t work out, she tells people at home that she was expecting a baby but it died. She doesn’t tell her deeply religious relatives that she committed what they see as the sin of ‘selling’ the baby. The crisis centre’s gynaecologist describes a very particular kind of generational conflict. The Russian army was long stationed in Alkhalzikhe and left behind large quantities of nuclear waste in the region after its departure. In this region near the Armenian and Turkish borders, there is an anomalously high incidence of reproductive illnesses and cancers. Those in their 50s, the parents of the surrogate mothers’ generation, have a very high incidence of infertility. This fuels a negative perception of the younger surrogate mothers who so “easily” fall pregnant. Despite trying repeatedly, we do not succeed in getting into the safe house, but we do manage to talk with one of its beneficiaries. This woman was beaten and abused by her alcoholic husband for five years before being left to fend for herself and her physically and mentally disabled son alone. What, we asked her, did she need to survive. “Boldness,” was her answer. As we leave Alkhalzikhe, passing the still fruit-bearing fig trees below the snow-bound mountain tops overlooking deep, dark valleys, we ponder the uses of boldness.

Easy money, heavy body

We return from the Turkish border with encouraging news: our sources have decided to trust us and will put us in touch with the surrogate mothers. But first we visit a medical centre in Tbilisi. Dr Oliko Murgulia receives us at the Zhordaniac clinic. She also contradicts Kukunashvili: while the head of New Life in Georgia advised against carrying out more than two surrogate pregnancies (while admitting that it can be difficult to police this), Murgulia told us that many surrogate mothers give birth four or five times, or as often as they can manage during their 20s and 30s. The surrogates are prepared hormonally for the implant. During the pregnancy, we are told, clinicians check not just whether the foetus is developing properly, but also when the surrogate mother is following doctor’s instructions and eating correctly. After birth, they check whether hormone balances return to normal and whether the menstrual cycle is resuming. But neither this clinic nor New Life in Georgia offers psychological or psychiatric care, even though Kukanashvili, a psychotherapist, concedes that it is necessary and hopes it can be provided in the future. Murgulia’s institution has a rule that the surrogate mothers shouldn’t be able to see or touch the child at all after birth: there is no contact after birth between the surrogate and the child, since the clinic’s staff believes this would be a mental burden for the birth mother. Speaking not as a doctor but as a woman, Murgulia tells us that this business is purely about money and that Georgian men often bring their own wives to act as surrogates. “I think these men exploit the women: the female body is a source of income for them,” Murgulia says. “Georgia is an undeveloped country, struggling with poverty. A Georgian woman with several children becomes a surrogate mother so as to have money to feed her own children.”

The fertility clinic is on the ground floor of a vast concrete building. It stands out from its surrounding. During a tour, we are shown where the eggs are extracted and where the implantation takes place, and we also see where they store frozen, unused embryos. After the interview we are offered coffee and cake. The clinic is staffed almost exclusively by women, we are told, and the procedures are carried out by first-rate American-trained specialists (“Have you any idea how hard it is to find a good embryologist nowadays,” I am asked).

“Often they just see the dollar signs on the cheque,” we are told. “We can hardly talk them out of coming back just a few months after giving birth. It’s easy money, after all - you can earn good money from four or five births.” This is not all there is to it, staff tell us, mentioning the joy felt by infertile couples when they finally get a child. Outside the hospital we witness a scene that highlights how children are valued in Georgia. An old car serving as a table, spread with food and drink and a loudly jubilant crowd around it. A young father is celebrating the birth of his child. Not via a surrogate!

Equal rights for surrogate mothers!

At the HeraXXI human rights group, director Nino Tsuleiskiri tells us that the current law on surrogacy is a source of tension for Georgian society and, unlike others we have spoken too far, she thinks it needs changing. The group even has a draft, which went to parliament for discussion in September. The biggest problem, Tuseleiskiri tells us, is that the system is untransparent and there is no systematic collection of data. That means one can only assume that the number of infertile women in Georgia is growing from year to year. Foreign citizens can arrange to have a surrogate birth with practically no restrictions (unless they are a same-sex couple), while Georgian women can only do so if they can prove that they are definitively infertile: for example if they have no womb. Georgian rights activists would like to make the system more transparent and available for Georgian citizens as well. We ask Tsueleiskiri if she has considered lobbying for a ban on surrogacy, given that the European Parliament passed a resolution in 2011 which said “surrogacy increases the trade in women and children as well as illegal cross-border adoption.” But she disagrees: a complete ban would just lead to more illegal activity. Such a radical change would not work. Who represents the interests of surrogate mothers, we ask? Tsuleiskiri points us in the direction of the ombudsman. Ekhaterine Shkiladze, the Deputy Public Defender of Georgia, outlines for us the law on healthcare and the relevant passages from the statute book, and adds that there is no system for recording or regulating surrogate motherhood in Georgia. There needs to be a national authority to do this, she says. Dubravka Simonovic, the United Nations’ special commissioner on violence against women warned during her last visit to Georgia that a lack of regulation in the field of reproductive medicine could lead to women being exploited and falling victim to violence. “We share this opinion,” the ombudsman tells us.

Dreams of a technical mother

We spend days talking with social affairs and legal experts, businessmen and -women, doctors, witnesses, observers. But we still have no answer to the question of what a woman who rents out her womb experiences, what a woman goes through if she gives birth over and over again in order to hand the child over to somebody else for a carefully arranged fee. We are getting only a very indirect impression of what the surrogate mothers think. Our interlocutors, whether for or against surrogacy, are very cautious in discussing this sensitive topic.

Magie is prepared to speak to us in public. We later learn that she has had so many problems in the past that she hardly cares what happens any longer. She is 34 and a cleaning lady, sometimes in work, often not. She became a surrogate five years ago because of her own one- and old children. “I wanted to feed them and see then,” she said. She admitted that she shut her eyes when she signed the surrogacy contract and had no idea what she was getting into. “My only concern was to make things good for my children. I only told my husband later, and he protested. But we couldn’t go back on it: if we’d cancelled the contract we’d have had to pay compensation,” she told us. The husband had one condition: nobody must find out that his wife gives birth to others’ children for mother. But, as is normally the case, it was impossible to keep the secret. Friends and relatives quickly found out, because she had to go repeatedly to the surrogacy centre for examinations. “They reacted very badly, cursing me and rejecting me. I was left on my own,” Magie tells us, sometimes laughing, sometimes looking away out of the window as she answers my questions. “We had a good relationship with the first couple: they were very fair, visiting us regularly, helping not just me but my whole family,” she said. She gave birth to a 2.5 kg girl, she tells me. After the birth, she breast-fed the child for a week: although the customers took the child immediately, they visited daily to have the child breastfed, while stressing over and over that the child was not hers. After the family left Georgia, Magie’s family tried to get back to normal. They did up their flat, which was in a state of dangerous decay, and the money made it easy to take care of the childrens. But the clinic came knocking again 11 months after the first birth. They called several times, urging Magie to try another pregnancy, since the first one was so successful. “I don’t know why I went into it a second time,” the 40-year-old admits. Currently she is pregnant with twins. Magie was recommended to the new parents by the previous couple as a “reliable” surrogate, and until the fifth month everything was going fine. But then she started to have problems requiring weeks of hospital treatment. She managed to keep going until the seventh month, but then she gave birth to underweight twins with bad health prospects. One of the babies died in Tbilisi, while the parents took the other back home to Israel. Magie was not given any further information. Two weeks after the Caesarian birth, she went to the surrogacy broker to ask about the surviving child and find out when she would receive the money. The company supported her and arranged the documentation, but then she received the information that the other child had also died - without any documentation. Then the brokerage sued on Magie’s behalf, but the clients counter-sued. They said the surrogate had concealed her health problems, and had thus had a problematic pregnancy, leading to the premature birth. The whole affair took place just as Patriarch Ilia made gave his sermon criticising surrogacy. The trial is still underway and Magie still hasn’t received her money. But she continues to remember the still living and the now dead child each year on their birthdays, even though they were not her own. Now she is pregnant again. “I hope that if I give birth to a third child, then I can get over everything I’ve been through,” she says. “I’m going to give everything, everything to this child,” she says with a smile, her eyes darting nervously. If she could go back, she wouldn’t be a surrogate again, she says. It is wonderful to give a child to infertile couples, she says, “but the most important thing is to understand that these children are just like all others.” She has a Georgian cross on her wrist, with the name of the patriarch on it, and she puts her hands in front of her mouth over and over as she argues with Ilia. “I am alone in this country, and I’ve lost everyone,” she keeps repeating, explaining the fate of surrogates.

When I handed the child over to the parents, only then did I realise what I’d done

We then talk to Tamar, who we are told “is less problematic”. She is a slender woman who wrings her hands as she arrives, more than an hour late. She asks us not to film her face or make her recognizable. Smiling, she repeats her formulaic introduction: “It’s wonderful to help childless couple have a baby,” she explains, adding that she is a teacher by profession who has not had a job for ages. Relatives recommended she try surrogacy when she wanted to split from her husband. He had beaten her for years. When they split up, she was left with nothing. The husband also prevented her from seeing her 10-year-old son. That’s when Tamar turned to surrogacy. Even those who had recommended it to her didn’t know. “It was hard, but I didn’t want to make a big deal of it,” Tamar added, saying that she felt like a mother again during the pregnancy. “I hadn’t seen my son for five years. I had a child while the baby was in my womb,” she said. She gave birth to twins in 2013 and to a boy in 2016. She was happy for nine months, and then came the trauma. “When I had to give the child to the parents, that’s when realised what I had done, that the whole thing can’t be undone,” she said. If she could go back, and if the law allowed it, she would have kept the child, she added. She met the foreign customers only once, at the embassy when they signed the papers. The episode illustrates the core role embassies also play in the surrogate parenthood programme. She has no other contact with the parents or the children. Just a few photos of one-day-old babies remain, although the parents could also have banned her from taking photos. She would try surrogacy again (I haven’t seen my son for five years, she repeats), but now she has to wait since she has recently had major surgery. The past four years and the two surrogate pregnancies have helped her free herself from domestic violence and buy herself a flat. Asked what she thinks of the term “technical mother”, she answers that she thinks of herself as a mother of four, and that, just like Magie, she too would like to keep in touch with the children she has given birth to, even though in her case the customers are against this. What would make her a happy mother, I ask her. “If I had my own child, who could stay with me.”

Whose is the child? It belongs to the person who takes it. That’s my final impression from Tbilisi. A big, strong man drives my taxi across the darkened city to the airport. The place is like a crime scene under investigation. There are policemen and sirens at every corner. Our driver barely notices as the loud Georgian folk music plays. He slaps the steering wheel and flirts aggressively. “Has something happened,” I ask. “Who are the policemen looking for?” “You know,” he answers. “We are hot people,” he says with a glance into the rear-view mirror. “We need control.”

***

This article was written with the professional help of Media Diversity Institute (UK).

Translated by Thomas Escritt